Aerial land scanning – pictures worth a million words!

Jamie Brookes is fascinated by the challenge of applying technology to understand the infinite complexity of the natural world. He believes drones should be seen as a tool to let us see the forest on a new scale and with a new perspective.

Cameras have been around for quite a while now. In the beginning, operators exposed glass plates with a sensitive coating to light for a predetermined amount of time. The chemicals would react with the light to produce a dark/light pattern on the plate of glass. The human mind interprets this abstracted pattern as being a familiar real-world scene, deriving a great deal of understanding from it. It is notably easier to show a person visual information than describe it to them.

The latest cameras use digital sensors of all kinds. They do not need delicate processing, are repeatable and enable imaging of previously unimaginable clarity. From planets to protons, we can image it all!

Meet the drones

Drones are small electrical aircraft which can be used to take photographs to accurately scan an area such as a woodland.

Operators will generally use the terms UAV (Unmanned Aerial Vehicle) and drones interchangeably. These small platforms allow you to hoist a sensor of your choosing above the area of interest and collect many forms of data with unobstructed line-of-sight.

Operators fly the drones over the area to be scanned in a regular grid pattern, taking photos all the way. It is usual to capture over 1000 individual photos of the area. Software stitches these photographs together into a three-dimensional model and two-dimensional images, known as an ‘orthographic’ image. GPS (Global Positioning System) readings allow the models to be located accurately.

Using drones to benefit our forests

There are a number of uses, according the woodland owner/manager’s goals. A few are described here.

Forest mensuration becomes exponentially easier. In contrast to traditional ground-based sampling, individual trees across the forest can be isolated and measured at the same time. Tree heights and stocking densities can be easily retrieved. Crown assessments can be made, including individual crown area. Emerging technology is achieving great results for automatic DBH (Diameter at Breast Height) measurement and improving volumetric predictions. Colouration differences in a monoculture plantation can reveal stressed or diseased trees. All these measurements are taken with accurate GPS positioning, allowing on-site navigation to any point of interest derived from the scans.

The orthographic image below shows true colour (left) and height data (right). Note the discoloured trees (circled), which might be hard to see from the ground within the dense stand. Also visible is the track condition – free of blockages.

Environmental monitoring over time becomes much more accurate. Large swathes of land can be scanned in less than one day. The scans can be used to produce a detailed, zoomable map with a detail resolution of less than one inch. Forests, peatlands, riverbanks, and coastal regions are good candidates for biannual monitoring. Repeat scanning over a forest environment allows us to compare the growth of stands over time – improving targeting of any remedial actions. In most cases, a three-to-five-year schedule is appropriate to capture stand performance.

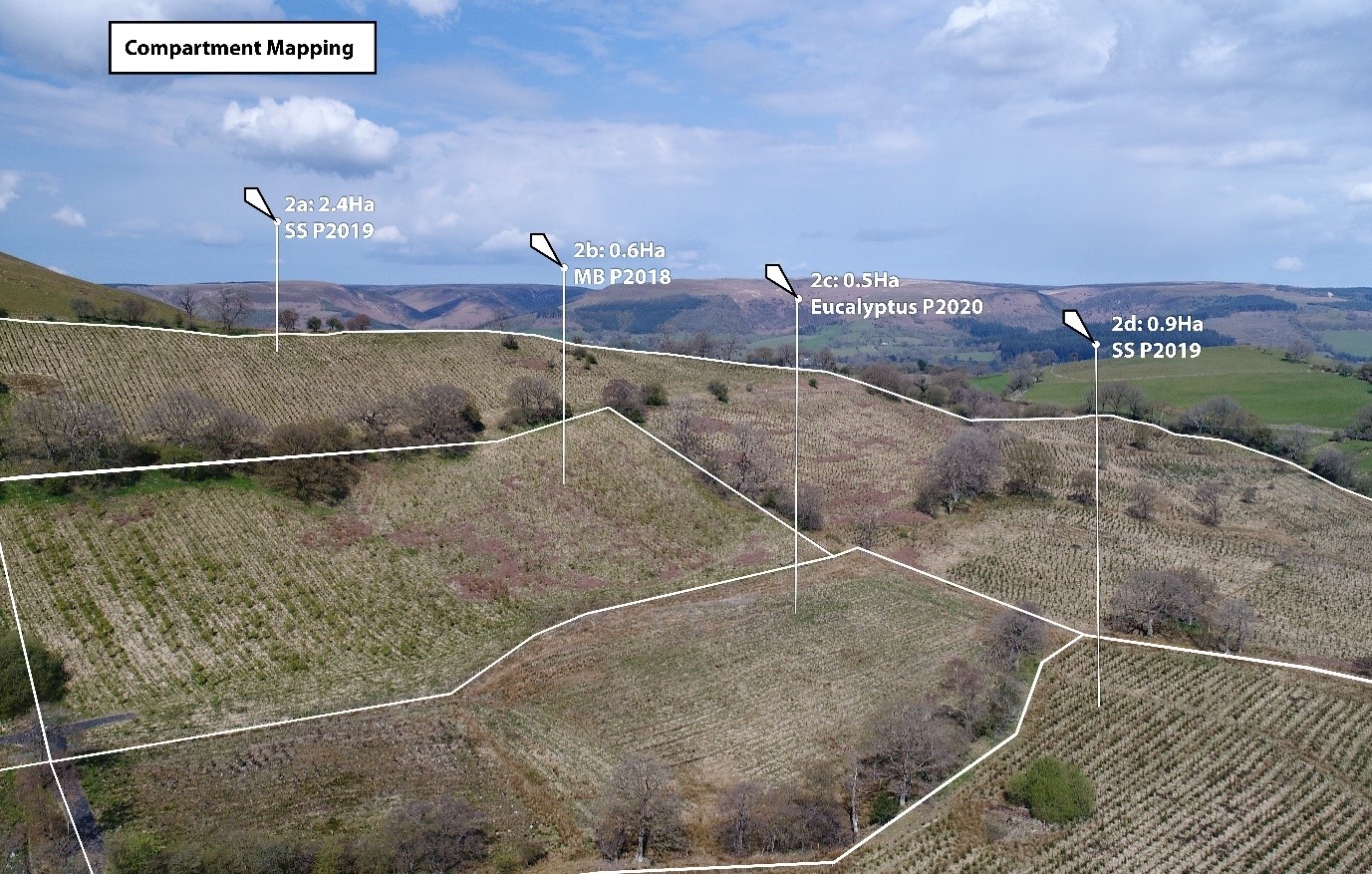

Information transfer can be conducted more clearly, using real-world imagery. Complementary information can be overlaid on the imagery to communicate site plans, strategies, or marketing materials. Detailed site plans can be overlaid on the scans to show you exactly what upcoming proposals look like on the ground.

Status reports can be provided for site management. From an operations perspective, felling operations and progress can be easily monitored. Capital works can be imaged, and areas measured. Compartment maps can be overlaid and modified with ease. Windblow assessments following bad weather (such as the recent Storm Arwen) can be quickly imaged and presented. All this data can be stored indefinitely to be retrieved for comparative purposes in the future. Once you have the scan data, you can use it repeatedly for new digital analysis techniques.

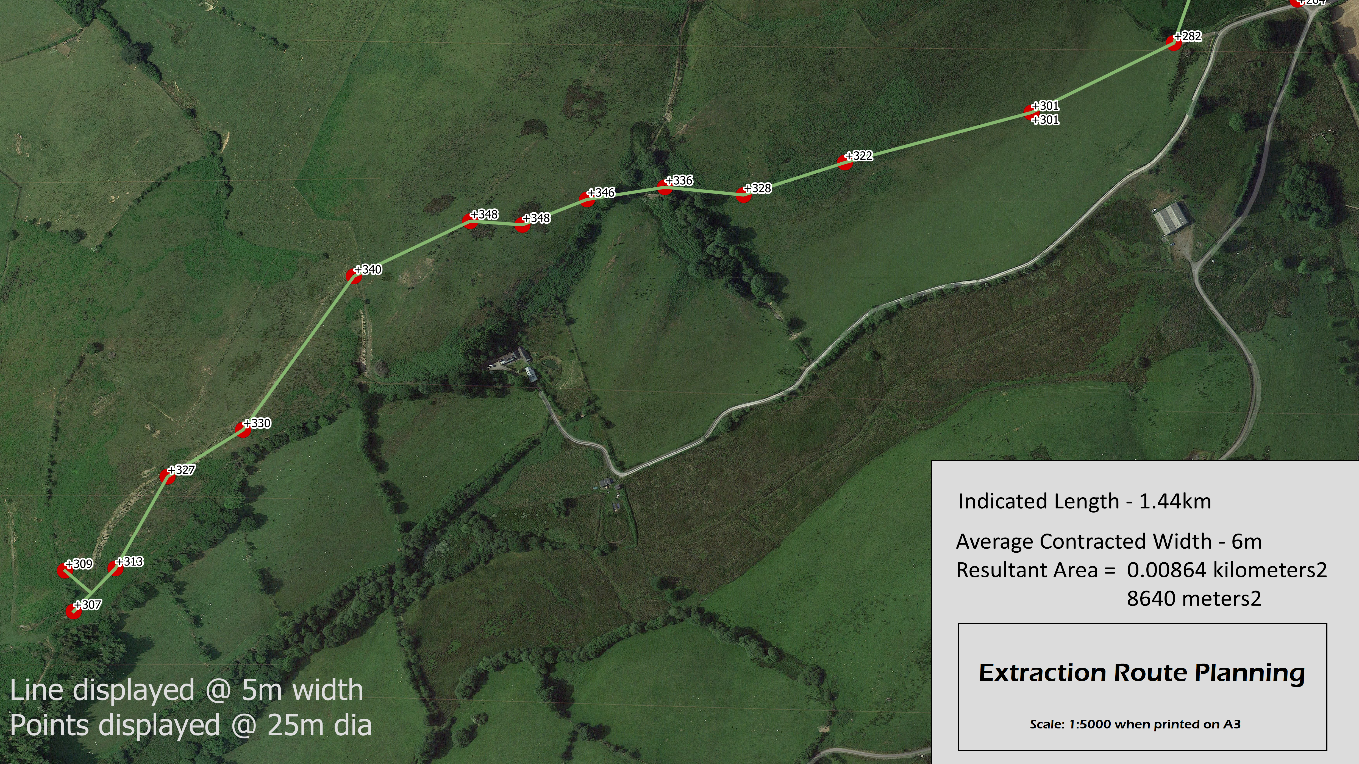

The image below shows how GPS positioning can be used to overlay a proposed extraction road. Areas can be taken into account for grant calculations.

Looking ahead

We can expect to see more prevalent use of two additional imaging techniques – multispectral and lidar.

Multispectral imaging uses sensors sensitive to light around the infrared range of the spectrum – outside of human sight. Vegetation reflects these frequencies of light differently under various conditions, which can be interpreted for clues as to health and vigour.

Lidar is a method of actively firing light at the ground and watching for the reflections. Millions of readings are taken which combine to form a 3D model of the target with strong understory detailing. For both technologies costs are currently high and there are few widely understood ways to interpret this increased complexity, although these barriers are likely to be overcome in time.

Is drone technology cost effective?

Ultimately the costs will be those tolerated by the market and depend on site size, location, and the services which fulfill the clients’ needs.

For providers, desk-based safety checks need to be performed upon quotation, followed by on-site risk assessments, and scanning time. The scans have then to be processed and the requested information generated. This can take one to many days according to the complexity. While quotation and repeat pricing structures currently vary by provider, you should expect costs in line with other semi-regular consultative service providers.

Regulation

UAV operators must register with the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) in certain circumstances, such as flights close to built-up areas or near uninvolved people. Most professional operators will be registered and insured.

Jamie Brookes

You could best summarise my life as a combination of oil and soil. I started my career and education in motorsport and passenger vehicle design. More recently, I have been fascinated by the challenge of applying technical methods to understand the infinite complexity of the natural world. I run a project called Landscan UK to advance this work.

For 2022 my goals are to continue to refine the use of UAV imaging across all woodland types, working with woodland owners on topics including natural capital assessments and continuous cover forestry.

For more information about how drones can be used contact me on 07762 477 431, enquiries@landscan.co.uk or visit www.landscan.co.uk.